AASL’s Standards for the 21st-Century Learner mandate that we equip our students with the skills they need to pursue lifelong learning. The Common Core State Standards, Next Generation Science Standards, and C3 Framework for Social Studies Standards all advocate for genuine student inquiry, and the best thinkers in education are demanding that students take a more active role in their education to make them competitive in the global economy. One practice that can prepare students for a lifetime of engaged learning is asking questions.

AASL’s Standards for the 21st-Century Learner mandate that we equip our students with the skills they need to pursue lifelong learning. The Common Core State Standards, Next Generation Science Standards, and C3 Framework for Social Studies Standards all advocate for genuine student inquiry, and the best thinkers in education are demanding that students take a more active role in their education to make them competitive in the global economy. One practice that can prepare students for a lifetime of engaged learning is asking questions.

What Makes Questioning a Literacy?

Literacies are how we make sense of the world; we read to gain knowledge, and we write to share new understandings. Asking and answering questions is also how we make sense of the world. It’s why young children ask so many questions—there’s a lot to make sense of and patterns about the world to discover. And yet, as children age they ask fewer questions.

The Right Question Institute finds that as children’s reading and writing skills improve, the number of questions they ask decreases, and, unfortunately, as the rate of questioning diminishes, so does the rate of engagement (Berger 2014, 44–45). It is our belief that teaching students to become fluent questioners also increases their engagement in learning.

The Right Question Institute finds that as children’s reading and writing skills improve, the number of questions they ask decreases, and, unfortunately, as the rate of questioning diminishes, so does the rate of engagement (Berger 2014, 44–45). It is our belief that teaching students to become fluent questioners also increases their engagement in learning.

When we think of someone who is literate we think of a person who can read and write—someone who can do only one or the other is not fully literate. To be question-literate a person must be able to both construct and understand questions. To construct a question students need to know what the parts of a question are and how to put those parts together to ensure that the question is asking for the answer they’re looking for. Just as students need to learn the alphabet and develop phonemic awareness, they need to learn different question words and how expert vocabulary and concepts are incorporated into questions. Understanding a question is different from answering a question; it means being able to form an idea of what an answer might look like and what type of information is being sought. Knowing how to go about answering a question is an important skill, and the first step in that process is understanding the question that’s been asked. As with any literacy, students need regular practice to develop questioning fluency and to learn how to comprehend and analyze questions.

To become question-fluent, students must understand how different types of questions operate. They need to practice asking and answering various types of questions so they can understand how different question lenses change the type of question being asked and the type of answer being sought—for example, “Which form of transitional justice is most effective?” versus “How does a society decide which form of transitional justice to use?”

Just as letters can make different sounds in different contexts, different types of questions serve different purposes depending on their context. “Which form of transitional justice is most effective?” requires a different type of inquiry when discussing transitional justice in general versus the narrower and more detailed inquiry that can be conducted when a specific case is being examined.

How Are Questioning and Critical Thinking Related?

Critical thinking is high-level thinking that requires us to analyze, evaluate, synthesize, or apply what we know. Its relationship with questioning is cyclical. Good questions—deep questions—are launching points for critical thinking. Questions, not answers, push us to think critically. As the cycle continues, critical thinking leads to more-nuanced questions. Questioning and critical thinking work together to further engagement, curiosity, thinking, and learning. As Richard W. Paul and Linda Elder have stated: “To think through or rethink anything, one must ask questions that stimulate our thought” (1999, 8). Answers are stopping points. Only when another question is asked can thought move forward.

Critical thinking is high-level thinking that requires us to analyze, evaluate, synthesize, or apply what we know. Its relationship with questioning is cyclical. Good questions—deep questions—are launching points for critical thinking. Questions, not answers, push us to think critically. As the cycle continues, critical thinking leads to more-nuanced questions. Questioning and critical thinking work together to further engagement, curiosity, thinking, and learning. As Richard W. Paul and Linda Elder have stated: “To think through or rethink anything, one must ask questions that stimulate our thought” (1999, 8). Answers are stopping points. Only when another question is asked can thought move forward.

Metaphors are often used by proponents of questioning, for example: questions are engines that drive thinking; questions are tools that help us dig deep into knowledge. We propose a rock climbing metaphor: questions are the foot- and hand-holds that help learners climb to new heights in their understanding.

Authentic questions are crucial for cultivating both the motivation and curiosity needed to scale those heights. As Ian Leslie said in Curious, “Asking good questions stimulates the hunger to know more by opening up exciting new known unknowns (2014, 103).” A recent study reported in Neuron concluded that curiosity positively affects memory and information retention (Gruber, Gelman, and Ranganath 2014). But curiosity does more than just aid knowledge acquisition; it moves thinking forward by closing kn

Authentic questions are crucial for cultivating both the motivation and curiosity needed to scale those heights. As Ian Leslie said in Curious, “Asking good questions stimulates the hunger to know more by opening up exciting new known unknowns (2014, 103).” A recent study reported in Neuron concluded that curiosity positively affects memory and information retention (Gruber, Gelman, and Ranganath 2014). But curiosity does more than just aid knowledge acquisition; it moves thinking forward by closing kn owledge gaps.

owledge gaps.

George Lowenstein, psychologist and behavioral economist from Carnegie Mellon University, has described curiosity as a “response to an information gap” (Leslie 2014, 34). To feel curious, to ask good questions, we must become aware of our own ignorance. It is that awareness that enables us to ask questions that will build our knowledge. If we return to our rock climbing metaphor, questions allow us to scale great heights by providing leverage points. They scaffold a learning journey, chunking it into pieces small enough to traverse but challenging enough to keep the learner interested. The beauty of student-generated questions is that they are individualized; each student determines her or his own path up the cliff face. While some may be prepared for a greater degree of difficulty, others may need to set a less-challenging course. When students become literate in the art of questioning, they have the tools they need for lifelong learning; they can set a course that guides and extends their thinking.

What Do We Ask Questions About?

Students who lack background knowledge can find inquiry-driven learning challenging. At first, their questions may focus on minutia of assignments’ due dates and requirements. (We’ve all encountered students who want to know what the source requirements are before they’ve even decided on a research focus.) It’s difficult to start asking questions before you have some context for what you’re asking about; if you’ve never seen the sky, you don’t ask why the sky is blue.

A range of different strategies can pique students’ curiosity, but one of my (Sara’s) favorites is the write around. I am deeply indebted to Buffy Hamilton for introducing me to write arounds and the work of Harvey “Smokey” Daniels and Elaine Daniels. Write arounds can take a number of forms, but the one I use most often when working with students to develop a research focus is text on text.

Text on text write arounds involve my laying out several passages of text and/or images on a large piece of chart paper and students’ collaboratively annotating the texts by quietly writing on the text and chart paper.

Text on text write arounds involve my laying out several passages of text and/or images on a large piece of chart paper and students’ collaboratively annotating the texts by quietly writing on the text and chart paper.

I recently used this strategy with a class doing research on literature related to the winter holidays. The collaborating teacher and I sought passages that would help shift students’ perspectives around familiar stories; if you know why the sky is blue, and suddenly the sky is green, you have new questions!

I have found this process especially useful in scaffolding the question-development process for students when paired with some of the strategies Ron Ritchhart, Mark Church, and Karin Morrison wrote about in Making Thinking Visible (2011). These strategies can expose gaps in understanding and provoke questions that will lead to further inquiry.

I have found this process especially useful in scaffolding the question-development process for students when paired with some of the strategies Ron Ritchhart, Mark Church, and Karin Morrison wrote about in Making Thinking Visible (2011). These strategies can expose gaps in understanding and provoke questions that will lead to further inquiry.

Carol Kuhlthau’s Information Search Process provides excellent guidance for the right times to intervene and provide some structured questioning for students—when to help students find a handhold on the cliff. Students who have hit a point of frustration and are asking “What do I research?” are at a point where they need questions asked of them, and they need scaffolded support for developing a research question.

How Do We Foster Questioning in Students?

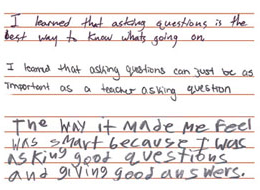

The first thing we can do to foster questioning is to make space for student’s questions. We can go a long way towards helping all students become literate questioners by giving them opportunities to ask questions and using those questions as springboards for learning.

The Question Formulation Technique (QFT) is another way to develop students questioning skills. Designed by Dan Rothstein and Luz Santana of the Right Question Institute, this process provides structure as students ask questions, analyze their questions, refine, revise and prioritize their questions. It is not enough just to have students pose questions, they also need to examine them critically. It is in the analysis and iteration of questions that the best questions emerge and that students develop their question skills. The QFT includes time for reflection on the process, encouraging students to think about their thinking and how it might apply to future learning.

The Question Formulation Technique (QFT) is another way to develop students questioning skills. Designed by Dan Rothstein and Luz Santana of the Right Question Institute, this process provides structure as students ask questions, analyze their questions, refine, revise and prioritize their questions. It is not enough just to have students pose questions, they also need to examine them critically. It is in the analysis and iteration of questions that the best questions emerge and that students develop their question skills. The QFT includes time for reflection on the process, encouraging students to think about their thinking and how it might apply to future learning.

For students who need help getting started with forming questions, it can be helpful to provide a list of question starts, such as “How would it be different if…?” and “What is the purpose of…?”. Scaffolding the question-asking process helps students develop fluency and confidence in asking questions and in understanding the questions asked of them. See our list of further resources for other strategies for scaffolding student questions.

The question-development process provides many opportunities for giving formative feedback while modeling questioning strategies. We can ask students why they think a particular question is useful or important, and what type of information they think they might find based on that question. Similarly, we can model our own questioning process when working with students and teachers by “questioning aloud” as we plan a lesson or a search strategy.

Sometimes student research is independent, but collaborative questioning can still be helpful. Students can be given time to develop their initial knowledge and questions on their topics through pre-search. They then present their findings to a small group, ending with a question of interest. Classmates listen and take notes, jotting down questions on sticky notes. Questions are shared with the presenter who then organizes and categorizes them, analyzing and revising them until a focus question emerges for research. This is a powerful tool both for practicing question skills and developing a better research question.

Regardless of How We Help Students Ask, Analyze, and Revise Questions, It Is Crucial That These Questions Lead to Something More.

Student questions can be used in many ways:

- as research questions to guide inquiry,

- for formative or summative assessments,

- as focuses for reading texts,

- as tools for problem solving,

- as driving questions for project-based learning, or

- as questions for Socratic Circles or Harkness Discussions.

Students will always need to be able to ask—and answer—good questions. By working with students to build better questions, we ensure that they will always be able to answer the question: “What do I want to know next?”

Jeanie Phillips is the librarian at Green Mountain High School in Chester, Vermont. A trained collaborative practices facilitator, she believes in the power of collaboration to foster deep learning. As a 2014/2015 Rowland Fellow, Jeanie is designing opportunities to increase student engagement and personalize learning in her library learning commons and in her school. Jeanie is also a member of AASL (American Association of School Librarians) and is currently serving on the AASL Standards and Guidelines Implementation Task Force.

This piece by Jeanie Phillips and Sara Kelley-Mudie was written for and published in the May/June issue of Knowledge Quest, the Journal of the American Association of School Librarians. The original content can be found here as printed in that publication.

Thank you to Jeanie and Sara for their permission to republish this piece here on the Rowland Foundation’s blog and to Meg Featheringham the Manager/Editor American Association of School Librarians for her consideration.

And finally, if you aren’t familiar with Carol Collier Kuhlthau’s work, Jeanie and Sarah recommend exploring her website.

Works Cited:

Berger, Warren. 2014. A More Beautiful Question: The Power of Inquiry to Spark Breakthrough Ideas. New York: Bloomsbury.

Daniels, Harvey, and Elaine Daniels. 2013. The Best-Kept Teaching Secret. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Gruber, Matthias J., Bernard D. Gelman, and Charan Ranganath. “States of Curiosity Modulate Hippocampus-Dependent Learning via the Dopaminergic Circuit.” Neuron 84 (2): 486–96.

Leslie, Ian. 2014. Curious: The Desire to Know and Why Your Future Depends on It. New York: Basic Books.

Paul, Richard W., and Linda Elder. 1999. Critical Thinking: Basic Theory and Instructional Structures Handbook. Tomales, CA: Foundation for Critical Thinking.

Ritchhart, Ron, Mark Church, and Karin Morrison. 2011. Making Thinking Visible: How to Promote Engagement, Understanding, and Independence for All Learners. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Rothstein, Dan, and Luz Santana. 2011. Make Just One Change: Teach Students to Ask Their Own Questions. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

Further Reading:

Berger, Warren. n.d. “How Can We Teach Kids to Question?” A More Beautiful Question. <http://amorebeautifulquestion.com/can-teach-kids-question> (accessed December 18, 2015).

Hamilton, Buffy J. 2014. “Moving from Our Mindmaps to More Focused Topics with Question Lenses and Musical Peer Review.” The Unquiet Librarian (October 27). <https://theunquietlibrarian.wordpress.com/2014/10/27/moving-from-our-mindmaps-to-more-focused-topics-with-question-lenses-and-musical-peer-review> (accessed December 22, 2015).

Heick, Terry. n.d. “7 Strategies To Help Students Ask Great Questions.” Teach Thought. <www.teachthought.com/critical-thinking/inquiry/8-strategies-to-help-students-ask-great-questions> (accessed December 23, 2015).

Ludwig, Sarah. 2015. “Using Question Lenses to Identify Conceptual Themes.” Sarah Ludwig: Sharing What I Learn about Education, Libraries, and Tech (February 2). <https://sarahludwig.wordpress.com/2015/02/02/using–question–lenses–to–identify–conceptual–themes> (accessed December 22, 2015).

Reblogged this on All Things Education and commented:

An excellent insight into the importance of questioning!